Indonesian SMEs Part II: Lack of data, coordination and will

By Masyitha Baziad November 12, 2015

- Republic lagging behind its Asean neighbours in terms of tech adoption

- Need for regulatory support, and comprehensive data to drive it

Untuk membaca berita ini dalam Bahasa Indonesia, silahkan klik di sini.

THE small and medium enterprise (SME) sector in Indonesia has proven to be quite resilient to the slings and arrows of external economic factors, and is doing its bit in providing jobs to Indonesians as well.

The country certainly recognises the value of SMEs, and is intent on developing and boosting the sector, with technology adoption and digitalisation being cited as key.

But these aspirations face on-going challenges.

The first is the availability of comprehensive and up-to-date data on the SME sector and its contribution to the country’s economy, according to the Association of Indonesian SMEs (Akumindo).

“This will be the priority for the Government and us,” its chairman Ikhsan Ingratubun told Digital News Asia (DNA), adding that a report would “hopefully be published in 2016.”

Indonesia’s Ministry of Cooperatives and SMEs had last released a whitepaper on the sector in 2013, which reported that SMEs had contributed to 57.95% of Indonesia’s GDP (Gross Domestic Product) and 16.44% of its foreign trade in 2011. The SME contribution comprised handicraft (30%), fashion products and accessories (29%), furniture (27%), food and beverage or F&B (10%), and health and beauty products (4%).

“I believe that the SME contribution to GDP has now reached 60%, and its portion of exports has reached 25%,” Ikhsan said.

He also argued that there was a lack of regulatory support to encourage and promote the sector, describing the existing legislation No. 20/2008 that covers SME empowerment and development as one that lacks any bite.

The law covers what qualifies a business to be defined as an SME, in terms of assets and profits. It also alludes to what kind of support an SME is entitled to in terms of financing, development, and land support, but falls short of making that support mandatory, he said.

“That 2008 regulation seems to have been crafted just for the sake of having legislation around SMEs,” he accused, saying that there are no specific articles in the law about what SMEs are entitled to in terms of financing, training, and development.

Ikhsan suggested the law be amended to first recognise the SME sector as the main economic pillar, not merely “one of the sectors that can” contribute to economic prosperity.

“By applying this approach, the articles inside the law will have more a more powerful impact on the development of the SME sector.

“More thought would be given on how to maximise the sector’s contribution to GDP, with the proper push from the central Government as well as local governments,” he argued.

Ikhsan also said the law has to be amended to include some kind of mandatory push as well as penalty for parties that refuse to support good SMEs, because currently, only SMEs are being held liable.

Poor technology skills

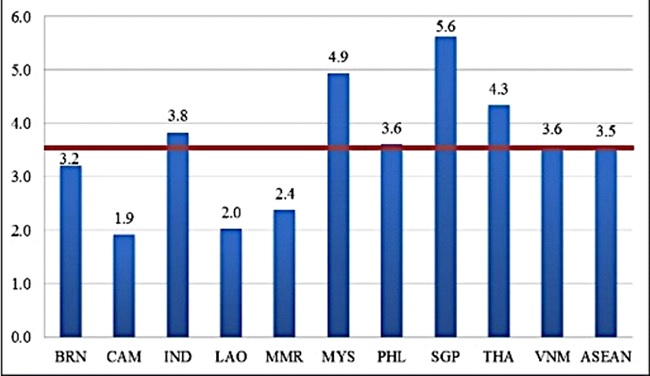

The Asean SME Index 2014 published by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and the Economic Research Institute for Asean and East Asia (Eria) in March 2014 shows that the competitiveness of Indonesian SMEs in terms of the implementation and transfer of technology is lower than that in Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand.

Gaps in promoting technology use and transfer stem from “the lack of a strategic approach to innovation policy for SMEs, poor provision of information on innovation support services, limited access to standard certification services, lack of technology support in universities, and few linkages between SMEs and R&D (research and development) labs and incubators,” the report stated.

This is further exacerbated by “poor protection and promotion of intellectual property rights, lack of broadband infrastructure, underdeveloped science/ industrial parks, lack of competitive clusters, and insufficient financial incentives in technology development and R&D activities.”

Among the reasons why Indonesia was lagging its Asean neighbours in this regard was because “innovation strategy elements are included sporadically in some policy documents without a consistent approach. Each ministry has its own plan.”

“There is neither synergy nor a system uniting all the strategy elements in the country,” the Index said.

As with Akumindo, the Asean SME Index 2014 also referred to the lack of information: “The website of the National Innovation System provides a database of innovation service providers and contains many types of innovation support programmes. Since it is just being launched, the information is still incomplete.”

The authors of the report also underlined how slow and unstable Internet connections in the country have hampered approximately around 60 million SMEs in Indonesia from going digital.

Last but not least, the Indonesian SME sector has not made optimal use of incubators.

“The number of incubator is still small. There is not even a virtual incubator available, and there have been no government regulations around incubators,” the report said.

By contrast, Thailand for example has a special institution for incubators called The University Business Incubator (UBI), coordinated by the Office of Higher Education Commission and the universities themselves.

Currently, UBI has established nine university networks covering 56 universities around the country.

In Malaysia, e-commerce has already been accepted as a new way of doing business, while its Government has recognised that the promotion of e-commerce and enhancing its use will enable Malaysian SMEs to compete more effectively domestically and in the global market, the report noted.

“All important and relevant information on SMEs can be accessed through the SME Info Portal which serves as the online one-stop SME node providing information on all programmes available for SMEs such as access to finance, markets, infrastructure, technology and advisory services and information.

“SMEs can also obtain relevant information through the SME Corporation Malaysia’s portal [which also] provides opportunities for SMEs to communicate through social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter for real time and up-to-date information on SME events or programmes, including issues confronting SMEs.”

But there is hope – even as DNA was preparing this report, the Indonesian Chamber of Commerce (Kadin) announced a one-stop SME portal at ukmmarket.co.id.

This free online SME marketplace would allow SMEs to go digital without having to worry about having to develop and maintain their own sites, or implement their own payment gateways, according to Kadin.

“We know that going digital is not a choice nowadays, it’s the way it should be,” said Ahmad Zaky, chief executive officer of PT Madani Sisfotel which operates the portal.

“We also know that many SMEs have very limited knowledge about going digital, and this portal will help them,” he said at the launch in Jakarta on Nov 11, adding that his company would be working with various agencies and ministries to create greater awareness, especially in rural communities.

Large enterprise help

Surprisingly, large enterprises in Indonesia are coming in to fill the gaps in the SME sector, although their ambitions are also being thwarted by a variety of factors.

For instance, in 2014, Google Indonesia kicked off its Gapura annual programme that provides training and seminars for SMEs on the ‘online way,’ part of the US technology giant’s efforts across the region.

The programme is supported by Indonesia’s Ministry of Cooperatives and SMEs, and various associations.

“Most Indonesian SMEs are still reluctant to go online because they do not understand [digital] or are not ready to penetrate bigger markets,” Google Indonesia’s Public Policy & Government Relations head Shinto Nugroho said in an official statement.

“Gapura helps SMEs find out more about online business, and gives them tips on optimising their websites,” he added.

PT Telekomunikasi Indonesia Tbk (Telkom) also has a similar initiative called Kampung UKM Digital (literally, ‘Digital SME Village’).

“The concept of Kampung UKM Digital is to utilise information and communications technology (ICT) in a comprehensive and integrated way in the business process, so that SMEs will be more advanced, independent and modern,” Telkomsel’s Enterprise & Business Services director Muhammad Awaluddin (pic) said at the launch in Bandung in June.

“The concept of Kampung UKM Digital is to utilise information and communications technology (ICT) in a comprehensive and integrated way in the business process, so that SMEs will be more advanced, independent and modern,” Telkomsel’s Enterprise & Business Services director Muhammad Awaluddin (pic) said at the launch in Bandung in June.

Muhammad said Telkomsel is also gathering IT volunteers, communities and partner companies to provide practical training for SMEs, and that it is targeting to ‘digitalise’ one million SMEs by the end of the year.

All these initiatives would come to naught, he however acknowledged, if the SMEs themselves lack the will and are not proactive in wanting to adopt technology.

“They must be passionate about improving their business, and must be willing to advance and able to compete in the global market,” Muhammad said.

Previous Instalment: Driving the economy

Next: Views from the ground

Related Stories:

The world’s for the taking: Google to SMBs

Blibli.com to bring Indonesia’s SMEs into the digital age

Made-in-Malaysia platform out to solve the SME tech dilemma

For more technology news and the latest updates, follow us on Twitter, LinkedIn or Like us on Facebook.