Social media: Vox populi when terror strikes

By Benjamin Cher & the DNA Team January 15, 2016

- The trending hashtags #SafetyCheckJKT and #KamiTidakTakut rallied the nation

- Danger of info overload and rumours; Facebook did not activate Safety Check

IN the wake of the Islamic State attacks on Jakarta on Jan 14, which left eight dead – four of them the attackers themselves [updated] – and 20 wounded (as at press time), social media again rose to the fore.

When there is any disaster or terrorist attack, the first instinct for people is to check whether their loved ones are safe, and to also try and figure out what is going on.

However, with the chaotic nature of such incidents, important news and updates become impossible to broadcast effectively. In this day and age of the always-connected smartphone, social media has become the platform to get the immediate facts, although the danger of rumour-mongering always lurks.

Indonesia is a social media powerhouse, with the Wall Street Journal reporting that the country had 69 million monthly active users on Facebook last year, while Statista put the number of Twitter users at 14.3 million.

As with the Paris attacks last year, when the hashtag #PorteOuverte was started by members of the public, the hashtag #SafetyCheckJKT quickly became a means of crowdsourcing information and identifying safe areas after the Jakarta attacks.

The origin of the hashtag was traced to Twitter user @ifahmi who first wrote:

(Translation: Dharmawangsa-Wijaya area is safe. Delta & Fortune are still open, as well as Kenanga & Kacamata #SafetyCheckJKT).

Even the Jakarta Government used the hashtag in its Twitter account:

(Translation: Hi citizens of Jakarta! Help report your safe locations with a photo and hashtag #SafetyCheckJKT. Stay safe!)

Jakarta residents heeded that call, tweeting out locations along with photos of where they were. Some tweeted without a picture, using just the hashtag with their current location.

The Jakarta Metropolitan Police’s Traffic Management Centre used its Twitter account @TMCPoldaMetro to give updates of the attacks and to also inform people of the traffic situation:

(Translation: 4:32pm Smooth traffic situation in Pancoran heading towards Cawang, likewise for the opposite direction.)

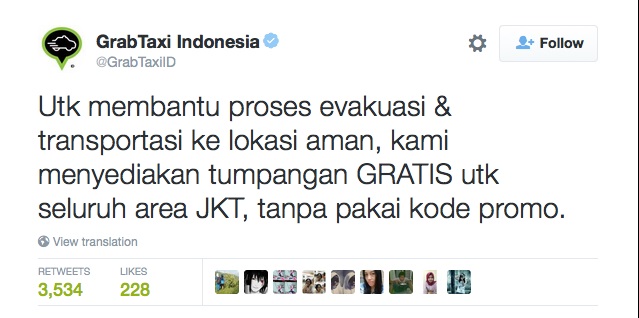

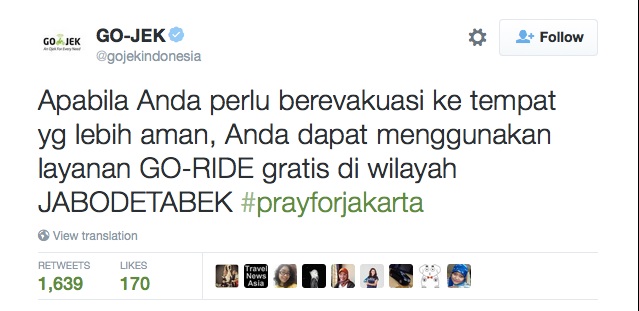

Ride-sharing startups like GrabTaxi and Go-Jek pitched in, offering users free rides to safe areas:

(Translation: To facilitate evacuation and transportation to a safe location, we are providing free rides for the whole Jakarta, without the need of a promo code.)

(Translation: If you need to evacuate to a secure location, you can use Go-Jek’s service for free in the Jabodetabek area).

Jabodetabek is the administrative term for the metropolitan areas of Jakarta, Bogor, Depok, Tangerang, and Bekasi.

Meanwhile, the #KamiTidakTakut (We Are Not Afraid) hashtag started trending too, as Indonesians declared they would not be cowed by such attacks.

Typical tweets were those asking their fellow citizens to stay safe and strong, or to send their prayers and hopes for the victims and their families.

Wheat from chaff

Besides Twitter, instant messaging app WhatsApp also came to the rescue of people wanting to check in with their loved ones and to receive updates.

Besides Twitter, instant messaging app WhatsApp also came to the rescue of people wanting to check in with their loved ones and to receive updates.

Tria Dinanti is an office manager working in Menara Thamrin, opposite Menara Cakrawala, the site of one of the explosions.

“My WhatsApp was flooded with hundreds of messages from family, colleagues, and friends,” she told Digital News Asia (DNA) via telephone.

“I couldn’t keep up trying to reply to them one by one, but the information exchange – especially on WhatsApp groups – wouldn’t stop. People were sending pictures and copied links of news articles,” she added.

The relentless flow of information had its drawbacks, one of which that she was unable to separate fact from fiction.

“Basically, the flow of information on WhatsApp alone was crazy – sometimes you didn’t know which ones were official and which one were rumours,” Tria said.

“I only started to use Twitter and Facebook two or three hours after the attacks, to let people know that I was safe and to also check the news that was popping up on my timeline,” she added.

Baskoro Wisnu Nugroho, who works in a school in Lippo Cikarang, also depended on Twitter and WhatsApp.

“First I would check Twitter for updated information … then my WhatsApp groups because they had information from friends and family,” he told DNA via instant message.

Reni Nugrahika Radhan, an employee with PT Petrosea, relied exclusively on WhatsApp. Indeed, he only found out about the attacks when a friend overseas messaged him to confirm the news that Jakarta had indeed been attacked.

The speed of social media is an advantage, according to Sri Mulyani, a stay-at-home mother from Manado, North Sulawesi, who has family and friends working in Jakarta.

“Before even the TV had live videos, they were all over Twitter,” she told DNA via telephone.

“Before even the TV had live videos, they were all over Twitter,” she told DNA via telephone.

“I checked my Twitter first because the platform is always quick with breaking news – its character limit means you get what you need very quickly.

“Then I would repost videos or photos from Twitter to my Path account,” she added, referring to the social media app that is very popular in Indonesia.

Sri also depended on instant messaging apps, rather than phone calls, to check on the safety of her friends and family in Jakarta.

“From there, I would then check WhatsApp or BBM (BlackBerry Messenger) groups just to make sure everyone I know in Jakarta was safe,” she said.

“Facebook came last – when things were calmer and if you wanted to read more detailed news on the attacks. I also used FB to express condolences and sympathy,” she said.

Now that the urgency is no longer there, Sri said she would be depending less on Twitter.

“The news agencies are airing all the amateur videos on national TV, so now I just keep monitoring more personal social media such as Path and Facebook,” she said.

Info overload and rumours

The use of social media as a broadcast medium during a crisis can be very effective, said Reza Caropeboka, communications manager at Endeavor Indonesia, an entrepreneur networking and mentoring company.

“In short, I’d say the social media is a very effective way to raise the alert about any topic in this, the world’s capital of social media, where most people are tuned in to their Paths, Facebooks and chat apps,” he told DNA via instant message.

However, verified information still remains an issue with social media, Reza said.

“My issue is the accuracy of the information. People can be very reactive and often pass on false information without checking whether it is true.

“And with the many messages and posts you are exposed to, it can be overwhelming.

“So I’d say social media and chat apps are effective in giving quick alerts, but we need to filter and sometimes wait till the dust settles to find out the truth,” he added.

Jagdish Singh, chief executive officer of integrated media company Campus Media Resources, concurred with Reza on the effectiveness of social media as a broadcast tool during crises.

“Social media is a ‘one-to-many’ medium, which makes it exceptionally efficient at broadcasting news and alerts during times of crisis,” he told DNA via email.

However, the power of social media to broadcast news needs to be used responsibly, argued Jagdish, also an occasional columnist with DNA.

“Take for example this case where New York residents read a tweet about an earthquake before feeling the tremors.

“This example is one that I use in my training sessions. All stakeholders involved in public crises should use social media responsibly to reduce casualties of all sorts,” he added.

However, the overwhelming amount of information on social media can leave many unable to see the veracity of news, an issue that even news sites and journalists are not immune to, according to Jagdish.

“Misinformation on social media is, unfortunately, a pervasive issue,” he said.

“People easily believe what they read on social media sites without making any effort to verify it, but what can you expect, when even credible news sites and journalists are taken for a ride by individuals due to lack of research?” he argued.

His example of the latter was the incident of tourists urinating on Mount Kinabalu in Sabah, when the ‘nudist’ Emil Kaminski had a field day with the Malaysian media by pretending to be one of the tourists concerned.

His example of the latter was the incident of tourists urinating on Mount Kinabalu in Sabah, when the ‘nudist’ Emil Kaminski had a field day with the Malaysian media by pretending to be one of the tourists concerned.

“So, who can you trust? One thing users should do is to first verify the information with major news sites before re-sharing it on social media or commenting – and to not make any rash decisions before that, if such decisions could affect your well-being,” Jagdish (pic) said.

“The problem sometimes is we see news --> make a silly decision --> make things worse,” he added.

For social media to become a key platform for information dissemination during crises, there needs to be more responsibility – but with the messengers, not the medium.

“Citizen journalism is a key theme for social media. The rise of affordable smartphones and data plans, and better cameras, equals a quicker pace of ‘reporting’,” said Jagdish.

“Social media is just the platform, and as with guns, it’s the users who need to evolve towards more responsible and ethical behavior.

“Like the cavemen who discovered fire, we’re all a bit Neanderthal now, but the next generation should be more responsible,” he added.

The disappearing FB

Facebook seems to be leading the way in how social media will evolve to deal with such crises, Jagdish argued.

“I expect other platforms to follow Facebook’s lead and launch initiatives which allow users to let their loved ones know that they’re okay, or to report on their condition, during a crisis,” he said.

But in the case of the Jakarta attacks, Facebook as a company seems to have disappeared.

The social media giant has been facing some flak over its Safety Check feature, which it first activated for the Paris attacks, but not for other attacks since.

Facebook has committed to activating the feature for other disasters, according to a Tech Crunch report.

However, it did not do so for Jakarta. What is threshold of disaster for either Facebook or Twitter to activate more servers or make a safety feature available?

DNA reached out to both companies to get their responses, but neither had responded at the time of writing. – With additional reporting by Masyitha Baziad & Ervina Anggraini (Jakarta); and Lum Ka Kay (Kuala Lumpur)

Related Stories:

Philippines typhoon: Tech companies pitch in

MDeC seeks a 'natural home' for its flood-aid system

Myanmar floods: Ooredoo provides aid, special code for customers to contribute

For more technology news and the latest updates, follow us on Twitter, LinkedIn or Like us on Facebook.