The world’s first mobile malware celebrates its 10th birthday

By Digital News Asia February 7, 2014

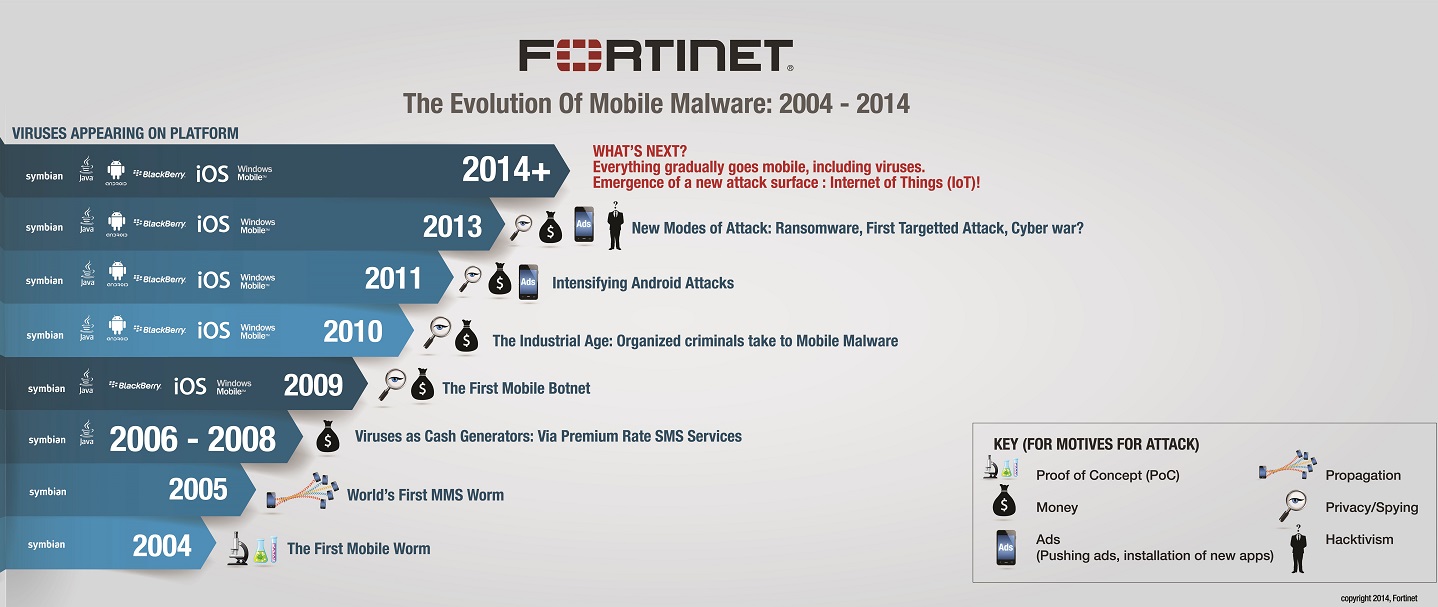

- 2014 marks the 10th anniversary of Cabir, the world’s first mobile phone malware

- FortiGuard Labs currently tracking 300+ Android malware families and 400K+ malicious apps

FROM Cabir to FakeDefend, the last decade has seen the number of mobile malware explode. In 2013, Fortinet’s FortiGuard Labs has seen more than 1,300 new malicious applications per day and is currently tracking over 300 Android malware families and over 400,000 malicious Android applications.

FROM Cabir to FakeDefend, the last decade has seen the number of mobile malware explode. In 2013, Fortinet’s FortiGuard Labs has seen more than 1,300 new malicious applications per day and is currently tracking over 300 Android malware families and over 400,000 malicious Android applications.

Besides the sheer growth in numbers, another important trend to note is that mobile malware has followed the same evolution as PC malware, but at a much faster pace, Fortinet said in a statement.

The widespread adoption of smartphones and the fact that they can easily access a payment system (premium rate phone numbers) make them easy targets which can quickly generate money once infected.

Furthermore, they have capabilities such as geo-location, microphones, embedded GPS (global positioning system) and cameras, all of which provide for a particularly intrusive level of spying on their owners.

Like PC malware, mobile malware quickly evolved into an effective and efficient way of generating a cash stream, supporting a wide range of business models.

In the following chronology, FortiGuard Labs looks at the most significant mobile malware over the last 10 years and explains their role in the evolution of threats:

2004: The first attempt

Cabir was the world’s first mobile worm. Designed to infect the Nokia Series 60, its attack resulted in the word ‘Caribe’ appearing on the screen of infected phones. The worm then spread itself by seeking other devices (phones, printers, game consoles, etc) close to it using the phone’s Bluetooth capability.

2005: MMS added to the mix

Discovered in 2005, CommWarrior would access the infected phone’s contact file and send itself via the carrier’s MMS service to each contact. The use of MMS as a propagation method introduced an economic aspect: For each MMS message sent, the phone’s owner would incur a charge from their carrier.

According to Fortinet, 115,000 mobile devices were infected and more than 450,000 MMS were sent without the knowledge of victims, showing for the first time that a mobile worm could propagate as quickly as a PC worm.

2006: Following the money

RedBrowser was designed to infect a phone via the Java 2 Micro Edition (J2ME) platform. The trojan would present itself as an application to make browsing Wireless Application Protocol (WAP) websites easier.

It was specifically designed to leverage premium rate SMS services. The phone’s owner would typically be charged approximately US$5 per SMS, another step towards the use of mobile malware as a means to generate a cash stream.

2007-2008: A period of transition

During this two-year period, even though there was stagnation in the evolution of mobile threats, there was an increase in the number of malware that accessed premium rate services without the device owner’s knowledge.

2009: The mobile botnet

In early 2009, Fortinet discovered Yxes (anagram of ‘sexy’), a malware which is behind the seemingly legitimate ‘Sexy View’ application.

Once infected, the victim’s mobile phone forwards its address book to a central server. The server will then forward a SMS containing a URL to each of the contacts. By clicking on the link in the message, a copy of the malware is downloaded and installed and the process is repeated over and over again.

The spread of Yxes was largely limited to Asia where it infected at least 100,000 devices in 2009.

2010: The industrial age of mobile malware

The year 2010 marked a major milestone in the history of mobile malware: The transition from geographically localised individuals or small groups to large scale, organised cybercriminals operating on a worldwide basis.

This was the beginning of the era of the ‘industrialisation of mobile malware,’ when attackers realised that mobile malware can easily bring them a lot of money and decided to exploit them more intensely.

2010 also marked the introduction of the first mobile malware derived from PC malware. Zitmo, Zeus in the Mobile, was the first known extension of Zeus, a highly virulent banking trojan developed for the PC world.

Working in conjunction with Zeus, Zitmo was used to bypass the use of SMS messages in online banking transactions, circumventing the security process.

Geinimi was one of the first malware designed to attack the Android platform and use the infected phone as part of a mobile botnet. Once installed on the phone, it would communicate with a remote server and respond to such a wide range of commands, such as installing or uninstalling applications, that it could effectively take control of the phone.

2011: Android, Android and even more Android

With attacks on Android platforms intensifying, 2011 saw the emergence of even more powerful malware.

DroidKungFu, which even today is still considered one of the most technologically advanced viruses, came into existence and had several unique characteristics. The malware included a well-known-exploit to ‘root’ or become an administrator of the phone – uDev or Rage Against The Cage – giving it total control over the phone and thereafter contacting a command server.

Plankton also arrived on the scene in 2011 and is still one of the most widespread Android malware.

2013: New modes of attack

2013 marked the arrival of FakeDefend, the first ransomware for Android mobile phones. Disguised as an antivirus solution, this malware works in a similar way to the fake antivirus on PCs.

It locks the phone and requires the victim to pay a ransom (in the form of an exorbitantly high antivirus subscription fee, in this case) in order to retrieve the contents of the device. However, paying the ransom does nothing for the phone which must be reset to factory settings in order to restore functionality.

What next: IoT

In the area of cybercrime, it is always difficult to predict what will happen next year and even more so over the next 10 years, Fortinet noted.

The landscape of mobile threats has changed dramatically over the past decade and the cybercriminal community continues to find new and increasingly ingenious ways of using these attacks for one sole purpose – making money.

Beyond mobile devices, the most likely future target for cybercriminals is the Internet of Things (IoT). While extremely difficult to forecast the number of connected objects on the market in the next fiveyears, Gartner estimates 30 billion objects will be connected in 2020 whereas IDC estimates that market to be 212 billion.

As more and more manufacturers and service providers capitalise on the business opportunity presented by these objects, it’s reasonable to assume that security has not yet been taken into account in the development process of these new products.

Will the IoT be ‘The Next Big Thing’ for the cybercriminal?

Related Stories:

Smarter, shadier and stealthier cyber-crime forces dramatic change

The 2014 security outlook for Malaysia: Symantec

Internet of Things: Installed base of 26bil units by 2020

Java exploits on the rise, Android malware break out of app stores

For more technology news and the latest updates, follow us on Twitter, LinkedIn or Like us on Facebook.